May 25, 2018

On March 27, 2018, I found out I had breast cancer. The lump that was “probably a clogged milk duct”, which turned into “probably just a cyst”, which turned into “most definitely a dilated duct”, turned into Invasive Ductal Carcinoma, one of the more common forms of breast cancer. Genetic testing, two MRIs, three oncologists, and seven weeks later, I had a bilateral mastectomy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

On March 27, 2018, I found out I had breast cancer. The lump that was “probably a clogged milk duct”, which turned into “probably just a cyst”, which turned into “most definitely a dilated duct”, turned into Invasive Ductal Carcinoma, one of the more common forms of breast cancer. Genetic testing, two MRIs, three oncologists, and seven weeks later, I had a bilateral mastectomy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

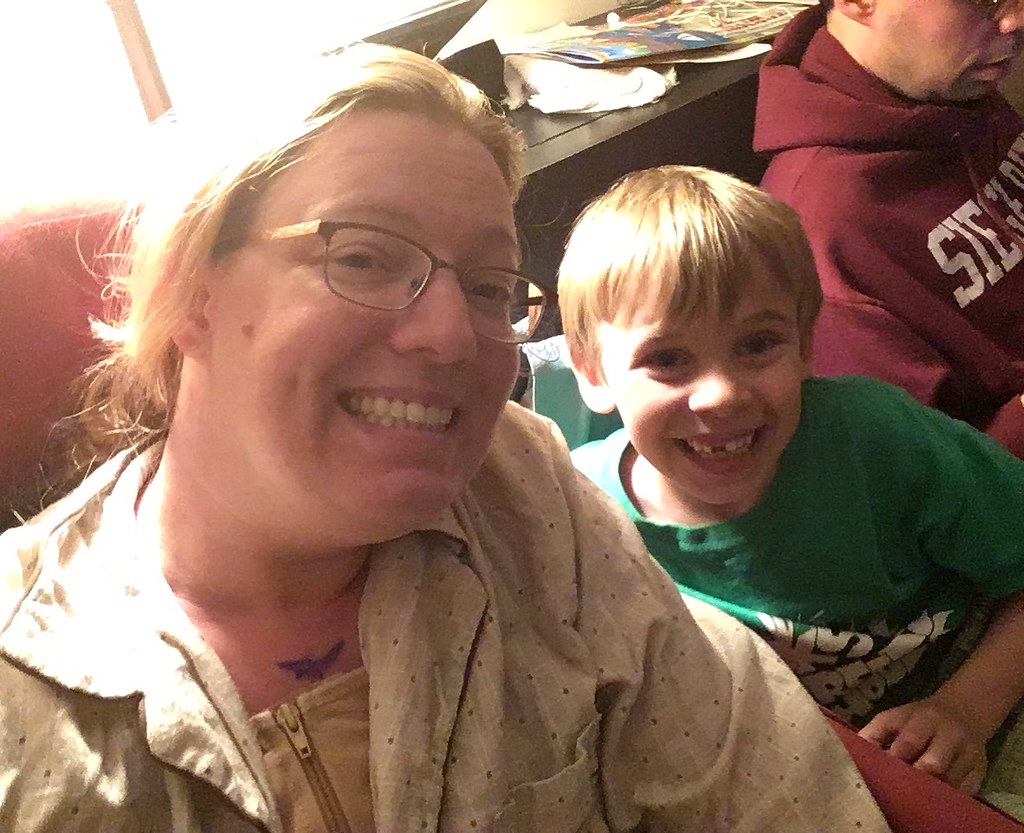

Did I mention that I’m only 35 years old? I have a two young boys, two and seven years old. I was still nursing. My husband and I had just bought our first real house with a real yard and a real furnace that needed to be replaced. I run a small non-profit that provides free postpartum support to families in Western Massachusetts, and was about to spearhead my first fundraising appeal. I was starting to look into training to be a Lactation Consultant. I had a plan.

Cancer was not part of the plan.

But lucky for me, and unlucky for this cancer (whom I named Phyllis), I’m a big fan of:

1) planning (even if it’s a brand new plan that I didn’t want any part of),

2) telling people to sit still and let others help them, and

3) taking my own advice. … ok, that last part is a lie. I’m terrible at taking my own advice. But to set a good example, I set into motion Mollie’s Cancer Postpartum Recovery Plan.

I know postpartum. I am a certified childbirth educator and trained as a doula, and my day job is supporting other parents while they navigate their postpartum journeys. “You deserve support” and “Let people help you” are heard several times a day at my workplace. I also had two of my own babies, with two VERY different postpartum experiences -- the first filled with isolation, loneliness, and depression, and the second filled with meal trains, competent care providers, and a Village of helpers.

So when it came time to tackle cancer, I did what I know -- I planned for a baby. I soon discovered a few similarities between the two which, while not making this process easy by any stretch, translated it into a language I could understand.

1. Doctors are human, every hospital is different, and your OB/Oncologist is not your friend.

I always tell my Childbirth Ed students the story of a couple I met while pregnant with my first. It wasn’t until 39 weeks that they discovered their hospital would not allow them to use most of the pain-relief techniques they had been practicing. I was shocked that they hadn’t been on their hospital tour until their 9th month, and hadn’t confirmed with their OB that everyone was on the same page with their birth preferences. Because of their experience, the rules in MY Childbirth Ed classes are:

1) Go on that hospital tour early, be the annoying one who asks a lot of questions, and then do it again at a different hospital. Learn what’s out there and available to you;

2) Interview your OB or Midwife, and then interview a few more. See what makes one different from another;

3) Make your care provider show their work. Ask questions, and make sure you understand WHY they’re recommending certain treatments, tests, or interventions. If you don’t like their answer, ask someone else. It’s OK to get a second opinion, or even switch providers, because this is YOUR birth, not theirs. They are not your friend, and worrying about offending them does not need to be part of the decision-making process.

After I got home from the appointment with my first oncologist, I turned to my husband and said, “I can’t figure out why I don’t like him. Was it because he kept saying annoying things like ‘You have cancer’, or was it because he didn’t seem good at his job?” The doctor did not know how things worked at the hospital -- he didn’t know where the gowns were, and kept giving conflicting instructions to his medical assistant. We dug into it a little, and found out that he was a locum tenens physician, basically a temp doctor, who wouldn’t be at this hospital for very long. Not really a comforting fact, considering I was 35 and would be dealing with continued cancer screenings for, hopefully, the next 50 years.

I set up an appointment with another oncologist at a different hospital, someone my dad knew. The difference in what he said was staggering -- we discussed MRIs, lymphedema, and his recommendation that I would need chemotherapy regardless of what they found, all things that the first doctor had not even mentioned.

The vast difference between my first two oncology visits convinced me I needed a third. By the time I saw my third surgeon and oncologist, I had my questions ready, and when they told me something that differed from what a previous doctor had said, I made them tell me why. I made them show their work. I left those appointments truly understanding my cancer, and what options were available to me. I weighed the pros and cons of each doctor and hospital, making sure to NOT factor in that surgeon #1 kept calling to see how I was feeling, or that oncologist #2 was a friend of the family. I decided on my care team based on what was best for ME and what made ME the most comfortable.

2. People want to help. They just don’t know how.

“Let me know how I can help” can be one of the most infuriating phrases to anyone recovering from birth. Not only did I just expel a fully-formed human from my body, am now solely responsible for keeping this human alive with juices secreted from my glands, am currently healing a massive wound inside my uterus from a placenta (which, by the way, I made from scratch) that was ripped from my body, and am dealing with a the myriad other potential ailments such as an abdominal incision, perineal stitches, and a pelvic floor that’s straining to keep all my internal organs where they’re supposed to be, but yes, let me check what we need from the store, Karen. I’ll get right on that.

The good news is that most people WANT to help, they’re just a little clueless about HOW to help. That’s where some planning comes in handy. I tell parents to keep a list of the household staples they often need on the fridge, so if someone offers, the list is ready for them. If you’re uncomfortable asking others to buy those items, have a gift card to the local grocery store loaded and ready for them to use. Websites like Mealtrain.com and Lotsahelpinghands.com make it pretty easy to organize meals, childcare, and other responsibilities among the (hopefully) vast network of people who like you. Also, tell people AHEAD of time that it’s ok to visit after the first week (or two or three, whatever you’re comfortable with), because you’re going to need help. I recently told a family friend how much it meant to me that she had come over after my second baby was born, that she had brought dinner and held him so I could take a shower. “How did you know that’s exactly what I needed?” I asked her. “Well,” she replied, “you TOLD us that’s what you were going to need, so I knew that’s what I needed to do.”

The main difference between planning for recovery from birth and planning recovery from cancer surgery is that I had nine months to plan for postpartum, and maybe 4 weeks to plan for surgery. Again, that’s where other people can come in handy. A dear friend said she wanted to be in charge of childcare -- we needed after-school dates for the big kid, and daytime childcare for the toddler in the weeks immediately following surgery. I gave her a list of my older kid’s friends, and SHE contacted their parents to set up play-dates. SHE created the childcare appointments in our lotsahelpinghands.com calendar, and all I had to do was share it around. SHE called people when she noticed there was a day that wasn’t covered. I was lucky that my husband was able to take time off work to be home with me immediately after the surgery (why I consider this lucky and not simply part of our healthcare system is a topic for another rant, er, I mean essay), but had he not been able to be home, many of the tactics I had used postpartum would have been just as useful post-surgery: label the kitchen cabinets so helpers know where to put away clean dishes, write instructions for the washer and dryer so anyone can do your laundry, and set some clear boundaries on when visit time is over (my husband and I came up with a code word: “Isn’t it time to check my drains?” was the signal that I was DONE and he needed to get rid of any visitors who had overstayed their welcome).

I think my cancer scared people. I was too young, too healthy, and dare I say too nice, to have cancer. There was nothing they could do take my tumor away, but they could make me dinner. They just needed to be told when and where (and that I really don’t like kale).

3. It’s ok to feel ALL the feelings.

To describe the variety of postpartum feelings would take up so much internet space, I’m not sure there would be room left for anything else. Joy, sadness, resentment, elation, guilt, pride, regret, relief, rage, loneliness, selflessness, unconditional and unending love, along with unconditional and unending fear. Some parents immediately fall in love with their babies, and for others it takes months. Some never want to leave their babies, and some can’t wait to get back to their previous lives. Some have an emotionally “easy” postpartum, some are tortured by depression, anxiety, and debilitating mood disorders, and the rest fall somewhere on the spectrum between the two extremes.

And those are all ok.

It’s ok to feel any and all of the feelings (though of course, mood disorders and feelings that get in the way of functioning need to be brought up with your care provider, so you can get support in managing them). Anyone who says, “No, don’t feel that way!” can go to hell. Feel it. These feelings are real, whether they’re socially acceptable or not, and they deserve to be recognized. If you dislike your baby today, that’s ok. If you think your baby is the greatest baby in the history of babies, tell the world. If you are loving being pregnant, basking in the beauty of breastfeeding, or stoked about your squishy postpartum belly, call me up and tell me. If you resent this parasite sucking every last ounce of energy out of your body, are “touched out” by this tiny human on you all day, and sobbing over the sight of your sagging figure, tell me that too. Because it’s all true for you.

About four days after my surgery, I lost it. I had been riding a wave of relief and oxycodone, much like the postpartum person rides the wave of adrenaline and oxytocin. But that day, just as the drugs wore off, the realization of what had just happened hit me. I had just cut off both my breasts. I had stitches across my chest, and tubes under both arms draining blood and fluid out of my body, because it had been cut open, scooped out, and sewn back together. I couldn’t hug my kids, couldn’t even snuggle with the toddler, because I had let these doctors mangle me. Oh, and did I mention the drugs had worn off? Between sobs about how I was a terrible mother because I needed other people to take care of my kids, how I was weak because clearly I needed more medication, and how I was somehow to blame for letting this happen to me, my husband (who, bless him, is not always the best at this “feelings” stuff) said, “It’s ok to not be ok. In fact, I’d be worried if you were totally fine with all this.” I had to get used to feeling relief and regret in the same breath, just as before the surgery I had been cycling between denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, and then back to denial again about my diagnosis. I was simultaneously brave and terrified, fierce and fragile. The same people calling me a survivor also had to see that I was also scarred. And I needed people who understood these feelings first hand, which leads us to our last point.

4. You’re going to need your Village.

It really does take an entire Village to raise healthy families. Babies are a 24-hour a day job, and it’s simply unreasonable to expect a parent to be able to care for themselves and a baby at the same time all by themselves. They need help. They need neighbors bringing food, extended family taking shifts of childcare, and people who have survived this journey nearby to show them the way. Part of the issue with families being alone in their nuclear bubbles is that not only are they managing the practical responsibilities of a parenting on their own, but they are also navigating the emotions of their lives in a vacuum. Parents need peer-to-peer support, to be heard and understood by someone who “gets it”. This is why “Mom Groups”, “Baby Playgroups”, and “Tummy Time” groups exist; it’s less about socializing the baby as it is about giving mom the chance to see other adults who understand her.

When I first got diagnosed, I felt a sudden isolation; not only did none of my friends really understand what I was going through, but every piece of information I was given felt like it was geared toward someone 30 years older than me. Late one night I was searching for articles about handling the responsibilities of parenting young children while going through cancer treatment. The only articles I could find were about how to TALK to kids about cancer, or how to manage when your child has cancer, but nothing about how to, say, get your toddler into his car seat when you’re not allowed to lift anything over 10 pounds. Finally, I found ONE article that profiled a young mother with breast cancer, and in it she mentioned the Young Survival Coalition, an organization dedicated to the critical issues unique to young women who are diagnosed with breast cancer. Finally, I had found my people. These women were young, some had young children, were early in their careers, and discussed things like fertility and breastfeeding.

In the Young Survival Coalition private Facebook group, I finally found the answers to those questions only a young woman with cancer can answer. Just as experienced mothers tend to send more practical baby shower gifts (“This is what you REALLY need”), these young survivors shared their recently-learned tips for dealing with cancer treatment as a young parents (“Yes, you WILL need childcare for the toddler for the first 6 weeks after surgery”). Better yet, I found a group of people who understood when I posted, sobbing over my keyboard, how it broke my heart that I couldn’t hold my child. They shared their stories, sent virtual hugs, and were there for me when I felt alone. There’s a special kind of support that can only be given by someone who’s been through it too.

My post-cancer-surgery bedroom looks a lot like my postpartum bedroom -- a nest of pillows, snacks and water bottles everywhere, a toddler being “gentle with mama”, and friends popping their heads in to say hi as they drop off dinner. The only thing missing is the baby, the squishy lump that I made from scratch, the happy ending to the pregnancy and postpartum journey. All I’ve got is a tumor in a jar … which, actually, I did make from scratch.

Mollie is the Co-Executive Director of It Takes a Village, a non-profit organization that provides free postpartum support to families in Western Massachusetts, and is the owner of Crafted Birth Childbirth Education.

No comments:

Post a Comment